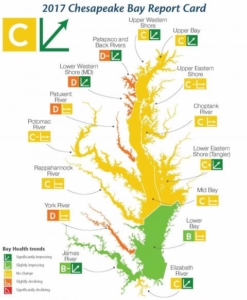

Researchers from the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science (UMCES) gave the Chesapeake Bay an overall grade of “C” in their annual report card. Although the “C” grade has remained constant since 2012, this is the first year that scientists have seen a statistically significant positive trend. Alexandra Fries, a senior science communicator at UMCES, told The Washington Post that “the long-term trend is statistically, significantly improving over time. There are no regions in decline.”

Bill Dennison, vice president for science application at UMCES, said in the same article, “we have seen individual regions improving before but not the entire Chesapeake Bay. It seems that the restoration efforts are beginning to take hold.”

Bill Dennison, vice president for science application at UMCES, said in the same article, “we have seen individual regions improving before but not the entire Chesapeake Bay. It seems that the restoration efforts are beginning to take hold.”

The Good News

Underwater grasses, dissolved oxygen, and total nutrients all showed positive trends. Grasses increased in almost all regions, most notably in the James, Choptank, and Rappahannock Rivers. Nitrogen and phosphorous scores were slightly better than last year and were strongest in the Lower Bay region. Both nutrients exhibited a gradient with higher concentrations in the upper reaches of the Bay and lower concentrations in the lower reaches.

Blue crabs, anchovies, and striped bass showed continued high scores. The report highlighted a Fisheries Index of 95%, the highest ever recorded.

Regions such as the James River, Elizabeth River, and Upper Western Shore showed improvements overall. The James got a “B-” and the Elizabeth received a “C”, their highest grades to date.

The Bad News

The overall health of the Bay is significantly improving for the first time.

Water clarity showed a negative trend, with several Bay regions making little or no progress. Water clarity did improve in six regions, but many other regions, such as the Lower Western Shore, have been experiencing “long term decline,” according to the report. Similarly to nutrients, clarity tended to exhibit a gradient pattern, with “murkier water in the mid to upper reaches and clearer water in the lower reaches.”

Chlorophyll a also showed a negative trend, with many Bay regions showing measurements that “frequently exceeded threshold levels.” The highest concentrations were in the Lower Western Shore, Upper Western Shore, York River, and Patuxent River, likely due to high nutrient availability.

Dr. Peter Goodwin, UMCES President, said in a press release that “While we can celebrate progress being made in the restoration of the Chesapeake Bay, we can’t take our foot off of the accelerator. It is critically important that we continue to invest in science and monitoring to improve management actions which ensure that the Bay continues on its path to recovery.”