Penn State’s Ray Najjar

Penn State Contributes to North American Carbon Report

Multiple Pennsylvania State University (PSU) scientists contributed to the Second State of the Carbon Cycle Report (SOCCR2), a massive collection of research on a carbon budget for North America. The first SOCCR report came out in 2007, so the recent report summarizes a decade of research developments. Ray Najjar, professor of oceanography in the College of Earth and Mineral Sciences, was the Science Lead Liason for four of the chapters: Terrestrial Wetlands, Inland Waters, Tidal Wetlands and Estuaries, and Coastal Oceans and Continental Shelves.

Other Penn State scientists also contributed heavily to the report. Maria Hermann of the Dept. of Meteorology and Atmospheric Science worked on the Tidal Wetlands and Estuaries chapter, and helped Najjar with the carbon budget. Ken Davis, of the same department, contributed to the chapter, Understanding Urban Carbon Fluxes. Alex Hristov, professor of dairy nutrition in the College of Agricultural Sciences, was the lead author of the Agriculture chapter.

Of the five science leads on the report, Najjar is the only one who does not work for a federal agency. He hypothesized that he was selected because of his involvement in the North American Carbon Program, where he has presented to multiple federal agencies on carbon cycle science. His research at Penn State focuses on coastal areas, and he currently has a NASA grant to study carbon cycling in coastal waters. His goal is to help create a carbon budget for tidal wetlands and estuaries in the continental United States. In a paper published last year, Najjar presented a budget for the entire east coast, and hopes to do the same for the Gulf of Mexico and the west coast in the near future.

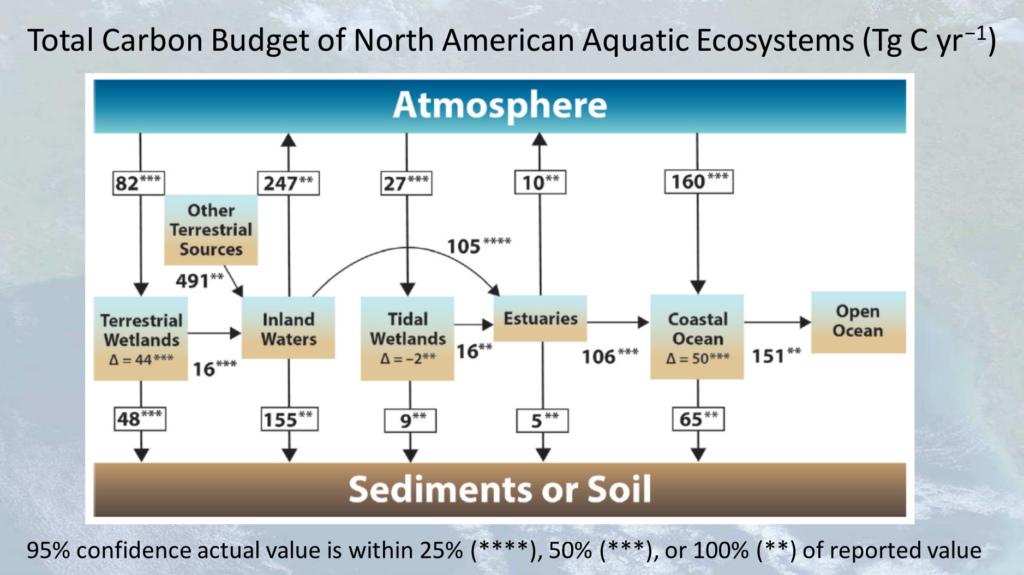

The carbon budget for North America created by Najjar for a talk he gave at the American Geophysical Union 2018 Fall Meeting

One of the most surprising findings in the report was that inland waters are acting as sources of carbon, which contradicts the first SOCCR report. The first report found that inland waters were a sink of 25 teragrams of carbon per year, whereas the new report found that they are actually a source of 247 teragrams per year. To put that into perspective, 1 teragram is 10^12 grams, or 1 million metric tons of carbon. “We emit about 10 petagrams of carbon per year globally per year by burning fossil fuels and through land use changes. That is 10,000 teragrams emitted every year,” explained Najjar. North America alone contributes 2,000 of those teragrams.

The report also provided further evidence for the importance of blue carbon – carbon captured by coastal and ocean ecosystems. Tidal and even terrestrial wetlands can store large amounts of carbon and are an important player in the carbon cycle. Najjar said that the report shows that “we have another reason to pay attention to these ecosystems, restore them where it is needed, and prevent other types of land use from degrading them.”

Najjar emphasized the importance of the carbon cycle in the Chesapeake Bay, explaining that “carbon is a great currency for studying a whole host of problems in ecosystems. You can’t really understand hypoxia without understanding carbon cycling.” He is currently working on a paper that investigates the air-sea exchange of carbon in the Chesapeake, and is excited by research from Hermann on carbon cycling in the Potomac River.

Several next steps emerged from the report, including reducing error bars and addressing thawing permafrost zones in North America. Carbon stored in frozen soils is slowly being released, and Najjar and many other scientists are worried that we might be reaching a tipping point. Another area of concern is the absorption of carbon dioxide by the oceans. “Our oceans are good at taking up carbon dioxide, but an acidified ocean is bad for aquatic life. This report provides another motivation for decreased emissions,” he explained.

Najjar was hopeful, however, about declining carbon dioxide emissions across the continent. Emissions from the United States peaked in 2006-2007, around the time that the last report came out. Since then, emissions have come down by about 10% due to less reliance on coal and increase fuel efficiency standards. “We have a lot more work to do, but it’s an optimistic finding that we can have a robust economy and declining carbon dioxide emissions at the same time,” explained Najjar. “We have really learned quite a lot and I’m proud of the work in SOCCR2.”