Harnessing the Power of Citizen Scientists

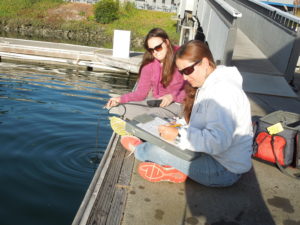

The SERC team deploying tiles into the San Francisco Bay in 2016. Credit: SERC/Marine Invasions Lab

Imagine working on a small team of field researchers and having to process 100,000 images. What used to take years and tons of funding to accomplish can now be done quickly and cheaply thanks to citizen scientists.

Researchers at Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) are harnessing the power of citizen scientists to identify critters in the San Francisco and Chesapeake Bay. The project, called Invader ID, is led by Alison Cawood, Citizen Science Coordinator, Brianna Tracy and Katherine Newcomer, researchers at the Marine Invasions Lab.

CRC covered the launch of Invader ID back in 2018, but the project has expanded and is now taking place on the Chesapeake Bay.

How Invader ID works

The team deployed 200 tiles in the San Francisco Bay and left them there for 3 months. Organisms, mostly invasive, attach to the tiles, showing the composition of the Bay. Then, they visited again and photographed every one, breaking up each picture into 50 parts, highlighting different parts of the image in each one.

Last year, the team uses a citizen science platform called Zooniverse to build an online space where volunteers could view all 10,000 pictures, answer a series of questions, and group the species in the pictures into 10 taxonomic groups.

The SERC team observes critters attached to a tile. Credit: SERC/Marine Invasions Lab

To help group the critters, the volunteers can look through categories like texture, pattern, and shape to help narrow down the answer. If volunteers are not sure what to choose, they can submit questions to the researchers, but they are encouraged to take educated guesses.

Each photograph stays viewable until 10 different people identify the panel’s organism. If 6 out of the 10 people identify the species in the same way, the image is officially removed. Since each of the 10,000 pictures must be identified 10 times, the team is looking for 100,000 identifications in total. 2,230 volunteers have already completed about 80,000 identifications in a year since the project’s launch.

The volunteers are often worried about choosing the wrong grouping, but the team says the process of confirming the pictures works well. “I’ve been really impressed,” said Tracy, on the volunteers’ identification accuracy. Newcomer added, “we did a comparison between us [the researchers] and them [the volunteers], and found that they were right 98% of the time,” and that the other instances were “so hard that even the scientists aren’t sure.”

“The volunteers are awesome,” added Cawood. “There’s lots of projects that have shown that if they’re trained correctly and the project is designed well, volunteers collect and analyze data really really well.”

Bringing Invader ID to the Chesapeake

The team hopes to bring Invader ID to every coastline, starting in the Chesapeake Bay. The team has developed a set of materials that volunteers can buy for around $20 to set their own tiles out.

Alone, the research team could only deploy tiles at 3-4 places per year. But with thousands of volunteer citizen scientists, the team could monitor tiles deployed at thousands of places.

Volunteer Sheren Riker assembled these two settlement panels—complete with tiles, dent removers, weights and ropes—on her dock at Church Creek. Credit: Sheren Riker

They developed a tile deployment system that can be built from materials found at any hardware or auto parts store. Using a tile, a dent remover, a rope, and a weight, tiles can be deployed just about anywhere.

When the volunteer returns three months later, the tile should be connected to the dent remover and hopefully covered with critters.

This summer, the team ran a pilot study of this method in the Chesapeake. SERC gave the materials to five volunteers, and about ten others purchased their own. By the fall, the team should know if the volunteer-led system could work at a larger scale.

The team is expecting the composition to look much different in the Chesapeake than in the San Francisco Bay. They are curious to see how differences in latitude and temperature might affect composition.

By collecting all of this data along the coasts, the team hopes they can measure changes in composition over time and detect new invasives as early as possible. Cawood noted, “If you don’t catch the invasive species early, there’s not really a chance [to manage them].”

The team is excited to expand the reach of this project and get more volunteers involved. “It’s expensive to be a field scientist,” said Tracy; “it’s expensive to fly people to a Bay to deploy panels, and pick them back up. If we can enable anyone with a cellphone to take a picture, that’s amazing.”

“And then kids nowhere near the water can help identify invasives,” added Cawood. Tracy laughed, “Can you tell we’re passionate about this stuff?”

Interested in helping out? Contact Alison Cawood or start identifying Invader ID photos today.