Sunrise over Kirkpatrick Marsh

Researchers at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science (UMCES), the University of Delaware, and Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) are investigating how ocean acidification could potentially compound existing problems in the Bay. A major problem already plaguing the Bay is caused by nutrient pollution. When fertilizer run off enters the Bay, nutrients in the fertilizer like nitrogen promote the growth of algae. When large populations of algae die, bacteria break down the algae, but use oxygen in the water while doing so. This creates area of low or no oxygen, called dead zones, that can kill nearby fish populations. The effects of nutrient pollution combined with ocean acidification create a “synergistic effect,” causing the Bay to become increasingly vulnerable.

Ocean acidification develops when carbon dioxide in the atmosphere dissolves in the ocean as carbonic acid, causing the pH of the water to drop. If this trend continues, by 2100 it could be difficult for crustaceans like oysters and sea urchins to build their shells. While blue crabs and algae might do well in these higher-acidity conditions, the food web will be disturbed if oysters and other crustaceans start to disappear.

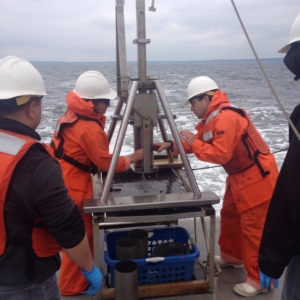

UMCES researcher Jeremy Testa collecting sediment cores

These effects are well-studied in the open ocean, where the ecology and chemistry is fairly uniform, and now researchers in Maryland and Delaware want to better understand these effects close to the coast in Bay estuaries. Last summer, a researcher at the University of Delaware, Wei-Jun Cai, found “a zone of increasing acidity at depths of about 30 to 50 feet across the Chesapeake” (Baltimore Sun). He found that deeper waters could be up to 10 times more acidic than more shallow water.

Jeff Cornwell and Jeremy Testa, researchers from the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, were on the team that took water samples for the University of Delaware project. Cornewell says that he is interested in “whether or not the acid levels rise sufficiently to hinder the production of juvenile oysters.” He and his team are currently investigating the carbon balance at an oyster sanctuary in Harris Creek, Maryland.

Overhead view of the marsh experiment.

While researchers at UMCES are observing chemistry and bivalves, SERC scientists are looking at plants and inorganic features. A team of SERC researchers led by Patrick Megonigal and supported by Whitman Miller have set up a series of heat lamps and plexiglass chambers in a marsh to study the effects of carbon dioxide, nutrient pollution, and increasing temperatures on grasses and invasive plants (pictured left). They are also observing how the marsh grows to match levels of sea level rise. Researchers are measuring the amount of carbon in the water coming in and out of the march via a gateway they are constructing.

The field set up for a SERC project monitoring a marsh

Experiments like these may help inform management efforts to decrease pollution and hopefully influence the dedication of more resources to understanding acidification. By studying multiple issues at once, scientists hope to better predict how problems like nutrient pollution and ocean acidification will affect Bay species.

Check out this Baltimore Sun article featuring all of this research.