Research in the Time of COVID-19

In the midst of great uncertainty brought on by the global COVID-19 pandemic, the Chesapeake Research Consortium’s (CRC) seven member institutions have shown resilience and adaptivity in conducting research, both in maintaining essential research but also in pursuing new and innovative research avenues. While we highlight how members of this consortium have worked diligently to continue research, we understand that the effects of this pandemic on education and operations at universities and research institutions are multifaceted and complex. We offer here a view into how some of the member institution researchers have been pivoting to our new pandemic realities: adjusting ongoing work, identifying new opportunities, and re-calibrating “business as usual”.

Adjusting to a different reality

One of the many impacts of COVID-19 on research has simply been not being able to be near others, from conducting fieldwork to being in the lab space. For some research, however, technology and ingenuity has made it possible for researchers to pivot and continue collecting data remotely.

One of the experimental chambers on the marsh. Credit: Tom Mozdzer.

Dr. Patrick Megonigal from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) was able to maintain four long-term experiments, including the original elevated CO2 experiment at the Global Change Research Wetland (GCREW), which recently entered its 34th year, without major disruption. Megonigal credited the ability to maintain these experiments without disruption due to experience with the government shutdown last year, which allowed SERC to efficiently identify essential programs to maintain during the pandemic, but also investments in technology made over the past several years, which allowed researchers to collect data and monitor experiments remotely. To operate these experiments, researchers continuously monitor the concentration of CO2 inside experimental chambers, the air and soil temperature in the warming experiments, water depth over the marsh and in the soil, and the chemistry of the water that floods and drains from the marsh. In the past, reading these data and checking for problems required someone to be at the site, but technology investments have allowed researchers to monitor these sensors from anywhere in the world where they have an internet connection. The sensors are connected to a small computer that collects and stores the data and allows staff to read the sensors in real time and to make changes to the experiments remotely. For example, if a severe storm is approaching the heaters in the warming experiment can be turned off, or researchers can see how high water levels are rising to know whether any field instruments are threatened. The system streams the data over to a cloud storage system, so any catastrophic loss of instruments does not also mean a loss of valuable data.

Adjusting to a virtual format doesn’t mean you can’t get outside! Photo: Chris Hein

Dr. Derrick Taff, an assistant professor in the Department of Recreation, Park, and Tourism Management (RPTM) at PSU, would normally spend summers in the field collecting data, which means intercepting visitors in outdoor recreational areas and asking them survey questions. While two of his field projects are delayed until next summer due to COVID-19, he was able to conduct a virtual survey with more than 1,000 participants across 47 states alongside the Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics. The survey examined how outdoor recreational behaviors and expectations of park management may be changing in response to the pandemic. “We’re all adapting to this new way of life. What’s not surprising but confirmed is how important outdoor recreation areas are and how we continue to seek these spaces for our well-being,” said Taff. Findings suggested that COVID-19 may be changing the way people participate in outdoor recreation, with many supporting increased measures to keep visitors safe, including limits on visitor capacity, social distancing rules, and requiring park staff to use personal protective equipment.

In-person surveys and engagement efforts have been impacted, with many indefinitely postponed. Dr. Anamaria Bukvic, an assistant professor in the Department of Geography at Virginia Tech and affiliate faculty with the Center for Coastal Studies, focuses on human geography, and more specifically, on population displacement and relocation due to coastal flooding. Her team had planned to travel this summer to the Eastern Shore of Virginia and the Hampton Roads area to conduct a household survey and interview stakeholders along the coast. All these interactions were put on hold due to COVID-19, but, “we quickly adapted and moved to other means of data collection,” remarked Bukvic. Instead of conducting in-person interviews, the team conducted virtual interviews with stakeholders, and instead of in-person surveys, the team transitioned to sending out mail-in surveys. “People are still concerned with coastal flooding and this issue is not going away. The science needs are still there and people are supportive of the research that has to be done to inform resilience planning in coastal communities,” explained Bukvic.

A makeshift lab for sediment processing and analysis in a garage. Photo: Chris Hein

Working from home took on new meaning for Dr. Chris Hein’s team from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS). Hein, a coastal geologist, has been able to continue his fieldwork season, after putting safety measures in place for conducting field and lab work. While his team lost April and May from their field season, the timescale of their research spans hundreds to thousands of years, so this relatively small delay in sampling would not affect the integrity of the research. In June, a select number of team members were able to go out into the field and collect the 80 ft. sediment core samples necessary for their research from the Eastern Shore of Virginia. The team members took great caution to self-quarantine before traveling and after returning, instead of processing and analyzing the cores in a lab, several students set up makeshift labs in their driveways or garages.

Emerging questions

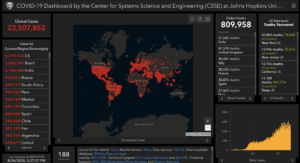

The Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Dashboard displaying global cases.

Johns Hopkins University (JHU) has been a global leader on clear and trusted data access from the beginning of the pandemic with the creation of the COVID-19 Dashboard, a go-to resource for recent data on the spread of the novel coronavirus. The open source dashboard, developed by Dr. Lauren Gardner and her team, is accessed more than a billion times a day and has quickly become the most reliable source of information for researchers, public health officials, and concerned citizens alike. The data from the dashboard is being used by a cross-disciplinary team of JHU researchers to develop data visualization tools, like animated maps and graphs, to show and explain trends to users in real-time, including a data-rich U.S. map that incorporates demographic and economic trends along with COVID-19 tracking data for each county in the nation. Some other tools include one that tracks the numbers of new cases of COVID-19 per day in the 10 most affected countries, which include the U.S., Italy, Spain, China, and the U.K., along with real-time feedback on the success of each country’s efforts to “flatten the curve”, and the cumulative cases of COVID-19 by date.

At Penn State University (PSU), Dr. Heather Preisendanz leads a project funded by the Institute for Sustainable Agricultural, Food, and Environmental Science (SAFES) investigating the presence of COVID-19 in the wastewater stream. Her team, partnered with the Penn State and University Area Joint Authority wastewater treatment plants, is monitoring wastewater for COVID-19 presence as well as pharmaceuticals known to be associated with diagnosis and/or treatment of COVID-19, such as antibiotics (to rule out COVID-19 diagnosis or to treat secondary infections), over-the-counter pain medication, and the experimental drugs, hydroxychloroquine and remdesivir. They are attempting to understand how widespread the disease is within the community and to investigate any potential agricultural and environmental impacts, as the treated wastewater effluent is spray-irrigated on farm and forest land. Their research will provide a better understanding of the level of local infection to local planners and PSU as they plan for the upcoming school semesters.

Surgical masks are emerging a potential source of microplastics in the environment as a result of increased use of disposable personal protective equipment.

Another emerging area of concern as a result of COVID-19 is the potential of increased microplastics in the environment as a result of increasing use of disposable personal protective equipment. Surgical masks are commonly fabricated with micro- and nanofibers made with plastic polymers, like polypropylene or polystyrene, which are a source of microplastic pollution. While there is not any current or ongoing research examining the connections between microplastics and COVID-19, Robert Hale at VIMS is beginning the experimental portion of a NOAA funded project this fall, after delays due to logistics and COVID-19, examining the interactions between microplastics and infectious haematopoietic necrosis virus (IHNV) in salmonid fishes, such as salmon and trout. For this large laboratory exposure experiment, Hale and his team will be exposing the fish to very small plastic particles (<20 microns). While the project is aligned toward plastics associated with fishing gear, the team has considered using surgical mask fibers as a potential source for plastic given how small the microfibers are.

New “business as usual”

The long-term implications of COVID-19 on the way universities and research institutions conduct business, research, and education are still changing and unknown, but we do know that “business as usual” has been forever changed. The ability to easily participate in a virtual event saves time, money, and reduces carbon emissions and can be just as engaging as in-person events. At SERC, the institution’s free lecture series transitioned to an online platform during the pandemic. When held in person, the evening lecture series would consist of around 80-100 people, but since the transition to an online series, has drawn 200 participants for each lecture. Kristen Minogue, the Media Relations Coordinator at SERC, has said that in the future, they are hoping to offer both in-person and virtual lectures. “Like everyone else, COVID-19 has been, at best, disruptive from an operational standpoint, but we’ve adapted and will be in a stronger position in 2021.” The University of Maryland’s Integration and Application Network (IAN) also made a virtual pivot this year. IAN hosts an annual press event to release its Chesapeake Bay Report Card. This year the event was virtual and by all accounts, went very well. And, we at CRC transitioned our biennial Chesapeake Community Research Symposium 2020 to an online event the past June and ended more than doubling the attendance compared to previous years. At the last in-person symposium in 2018, there were 210 people in attendance. At the virtual symposium in 2020, 495 people attended! This has sparked discussion about including a virtual component to future symposia regardless of the pandemic situation.

We’ve provided a glimpse into how CRC member institutions are adjusting and hope that those reading this can find inspiration from how their fellow researchers have adjusted. The pandemic has not diminished the need for research and education but highlighted the importance of its continuation. The tools and resources that are developed as we adapt and adjust to move forward will only strengthen our progress in meeting research goals and new demands.